Meeting Minutes October 16, 2025

I hope you had a good summer, with lots of time to enjoy gardening. As shorter days signal a change of season, Gail and I are making plans for the rest of the year.

Garden Ecology League Fall Meeting, October 16, noon to 1 pm

Summer is a prime field season for Garden Ecology Lab studies. Gail will share progress and answer questions during our meeting on October 16. Please see the attached agenda for details and the newsletter for background information about the garden pollinator plant study.

Garden Ecology Briefs have grown to 19

As you know, we produce Garden Ecology Lab Briefs to further the Lab’s education mission.. Each brief translates Lab research into 3 segments: What was the question? What did we learn? How does this inform gardening?

Check out all 19 briefs here on the “For Gardeners” page of the Garden Ecology Lab website. Individual links are listed below for direct access.

Pollinators on Native Plants and Native Cultivars

- Layering Garden Plants for Pollinators

- Gardeners Do Not Prefer Native Cultivars

- Breeding Native Plants has Ecological Trade-Offs

- Plant Parentage Complicates Native Status

- Protecting Bulbs from Gophers

- Pollinators on Native Cultivars versus Native Plants

- Exploring Color through the Eyes of Bees

- Leafcutter Bees have Petal Preferences

- The Diets of Specialist Bees

Insects Associated with Pacific NW Native Wildflowers

- Gardeners Value Ecological Beauty

- Supporting Diverse Bees with Native Plants

- Supporting Biocontrol with Native Plants

Garden Soils

- Common Garden Soil Bacteria Microbes

- Gardeners Overapply Compost and Fertilizer

- Cultivating Garden Soil Bacteria Microbes

Garden Bees

Garden Hoverflies

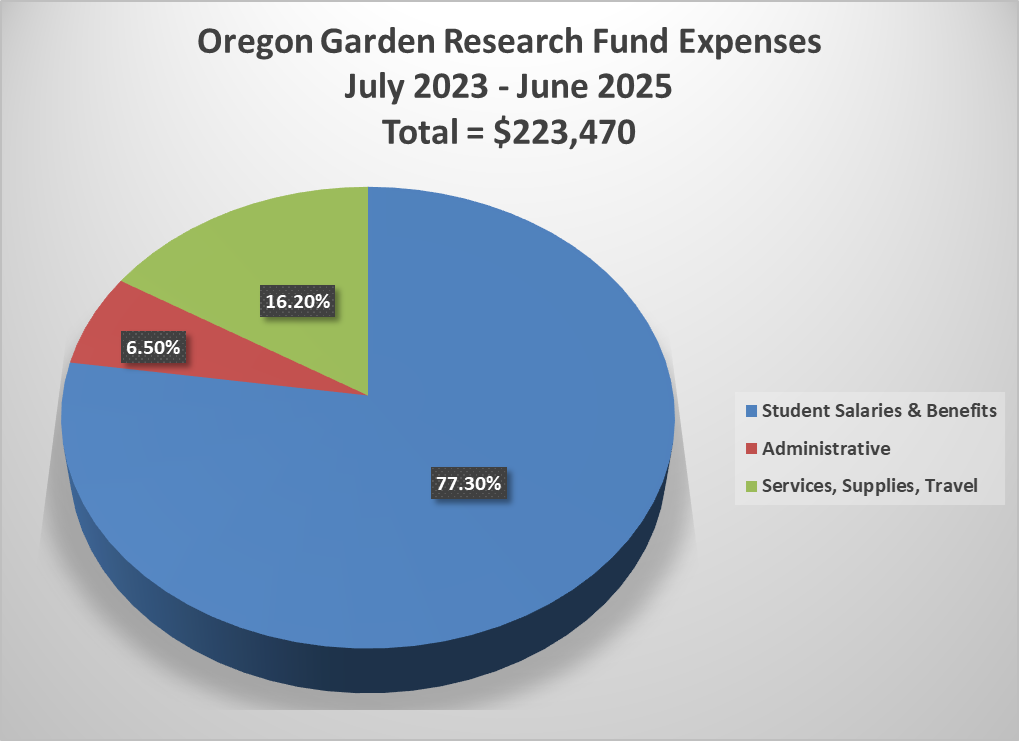

A Snapshot of the Oregon Garden Research Fund

The Oregon Garden Research Fund began in October 2023. To date, it has received $271,725 in donations. Over the past two academic year (July 2023 – June 2025), the fund has paid for research at the Garden Ecology Lab. Below is a summary of these expenses.

Sherry ShengChair, 10-Minute University™A short-cut to research-based gardening know-how delivered by Oregon State University Master GardenersMember, Campaign for Oregon State University, CAS Campaign Cabinet

GARDEN ECOLOGY LEAGUE NEWSLETTER

Fall 2025: Pollinator Garden Plant Study

Thank you for your support of the Garden Ecology Lab, and welcome to the 4th edition of the newsletter for Garden Ecology League members. This biannual newsletter will keep League members informed of research and share other news of interest. In this issue, I highlight Taylor Janecek’s work on pollinator garden plant communities, which will be the focus of our October 2025 Zoom call. However, you can get a glimpse of what has been happening across multiple Garden Ecology Lab studies this summer, by visiting this link to the ’Science Behind the Scenes’ series on our blog.

Pollinator Garden Plant Study Overview

Although there have been studies of residential and community garden flora in other areas of the world (United Kingdom1) and the U.S. (Salt Lake City2, Los Angelos3, Minneapolis3, Boston3, Baltimore3,4, Phoenix3, 5, and Miami3) no one has yet quantified plant communities in Pacific Northwest gardens. We thus decided to inventory the plants growing in Western Oregon pollinator gardens.

Our lab’s previous work guided our decision to focus on pollinator gardens. But we were also influenced by logistical constraints. The typical suburban yard (minus the footprint of the house) varies between 5,000 square feet (ft2) to 10,000 ft2, whereas many pollinator gardens represent one piece of an entire garden space. In fact, the pollinator gardens we documented ranged from 34 ft2 to 1,488 ft2 in size, with a mean of 483 ft2 and a median of 365 ft2. The relatively smaller size of pollinator gardens (about 10-20X smaller than an entire yard or garden space) made it possible to collect data with the time and resources we had available. However, this also meant that we chose not to study gardens where the entire space was managed as a pollinator garden, including an exceptional 4,551 ft2pollinator garden in Portland. However, exceptional gardens tend to be outliers. Our approach better represents what most people might have in a Western Oregon pollinator garden.

Our goals with this study are to better understand:

- The diversity and types of plants that can be found in pollinator gardens. We anticipate classifying each plant by their life cycle (e.g. perennial, annuals), stem type (e.g. woody, herbaceous), leaf type (e.g. evergreen, deciduous), growth habit (e.g. tree, shrub, groundcover), and origin (native or introduced, including cultivars) to see if there are any discernable patterns in pollinator garden plant communities.

- The extent to which plants found within pollinator gardens overlap with the recommendations from published pollinator plant lists, including those from OSU (e.g. Oregon Flora, Oregon Bee Project, OSU Extension), non-profits (e.g. Bird Alliance of Portland, Xerces Society), and local nurseries or garden stores. We hypothesize that a minority of the total number of plant species found in pollinator gardens will be found on local plant lists, but that the numerically abundant/common plants will be those found on published pollinator plant lists.

- The types of pollinator species that each plant is known to support, based upon published research, as well as the number and types of plant species for which no published research exists. We hypothesize that a minority of plant species found in pollinator gardens have data supporting their utility as a pollinator plant. Instead, we suspect that most plants have anecdotal or no data to support their categorization as a pollinator plant.

Study Methods

Taylor worked with our summer 2025 undergraduate students (Reed Manderfield, Georgia Vatcoskay, and Anna Janowski) to document the plant community in 26 pollinator gardens: 10 in the Corvallis/Albany, 10 in the Portland, and 6 Eugene. These 26 gardens were selected for study from the pool of 85 gardeners who responded to an online call for study sites. Twenty-six sites were disqualified from further consideration, because the respondents gardened outside of Oregon or were not agreeable to having students study their garden. Taylor visited the remaining 40 of the remaining 59 sites that were within a reasonable driving distance to ensure that they were safe, accessible, and appropriate for the scope and scale of our study. After the site visits, Taylor and I worked together to select sites that represented an array of gardening styles, in three clustered regions.

The crew spent a total of 14 days visiting gardens. Once on site, they measured the total area dedicated to the pollinator garden, took digital vouchers of each plant type within a garden, and counted or subsampled the abundance of each plant type by counting individual plants or stems. Digital vouchers were uploaded to an iNaturalist project page we set up for this study. We are in the process of identifying and categorizing each of the 921 digital voucher photos. Note that many of our observations are still awaiting confirmation and vetting from horticulture professionals. Thus, the preliminary results that we share in this newsletter may slightly change with improved identifications.

Preliminary Results

Thus far, we have documented nearly 300 unique plant types (genera and species) across 26 pollinator gardens in Western Oregon. The 20 most-common pollinator plant taxa are listed in the table, below, along with their native status.

| Common Name | Latin Name | Native Status1 | Native Range1 | % of Gardens Where Present (n=26) |

| Yarrow | Achillea millefolium | Native and Introduced | Broadly native across North America. Also considered introduced, since A. millefolium L. is of Eurasian origin and virtually indistinguishable from native varieties. | 46% |

| Wooly Sunflower | Eriophyllum lanatum | Native | Regionally native, West of the U.S. Rocky Mountains. | 46% |

| Selfheal | Prunella vulgaris | Native | Broadly native across the U.S. | 38% |

| Farewell-to-Spring | Clarkia amoena | Native | Locally native to the Western U.S. states. | 38% |

| Douglas’ Aster | Symphyotrichum subspicatum | Native | Regionally native to Western North America. | 38% |

| Meadow Checker-Mallow | Sidalcea campestris | Native | Locally native to Oregon and Washington. | 38% |

| California Poppy | Eschscholzia californica | Native | Broadly native across the Western U.S., with limited pockets of native populations in the Eastern U.S. | 35% |

| Purple Coneflower | Echinacea purpurea | Introduced | Regionally native, East of the U.S. Rocky Mountains. | 31% |

| Bluehead Gilia | Gilia capitata | Native | Broadly native across the Western U.S., with limited pockets of native populations in the Midwestern U.S. | 31% |

| Oregon Grape | Mahonia aquifolium | Native | Broadly native across the Western U.S., with limited pockets of native populations in the Midwestern U.S. | 31% |

| Fireweed | Chamaenerion angustifolium | Native | Broadly native across North America. | 31% |

| Borage | Borago officinalis | Introduced | Native to the Mediterranean region. | 27% |

| Snapdragon | Antirrhinum majus | Introduced | Native to the Mediterranean region. | 23% |

| Grand Collomia | Collomia grandiflora | Native | Broadly native across the Western U.S. | 23% |

| Showy Milkweed | Asclepias speciosa | Native | Broadly native across the Western U.S. | 23% |

| Baby Sage | Salvia microphylla | Introduced | Native to Mexico, Guatemala, and the SE U.S. | 23% |

| Western Columbine | Aquilegia formosa | Native | Regionally native, West of the U.S. Rocky Mountains. | 19% |

| Winecup Clarkia | Clarkia purpurea | Native | Regionally native, West of the U.S. Rocky Mountains. | 19% |

| Garden Nasturtium | Tropaeolum majus | Introduced | Native to Andes Mountain area of South America | 19% |

| Rose Spirea | Spiraea douglasii | Native | Locally native to Western Oregon and Western Washington. | 19% |

1Native status and Native range were determined using the USDA PLANTS database: USDA-NRCS, 2022. Plant List of Attributes, Names, Taxonomy, and Symbols, https://plants.usda.gov/ accessed September 18, 2025.

Preliminary Impressions

I am somewhat surprised that no single plant taxa was present in the majority of gardens that we studied. I think this speaks to the variety of pollinator plants available for purchase in retail markets, as well as the fact that gardening allows for individualized and creative expression. Even though all of the gardens we sampled had a common goal (to support pollinators) the plant community found within each garden was unique. In fact, 93% of the plant taxa that we documented were only found across 4 or fewer gardens.

Fourteen of the 20 most common plants found in pollinator gardens were native to our region. This may be a biased byproduct of our lab’s previous work on native plants, and the gardeners who were most likely to receive our request to participate. However, it may also be since many gardeners conflate gardening for pollinators with gardening with native plants.

I was also surprised to see so many edible plants in pollinator gardens, including tomato, beet, apples, sweet potato, and blueberries. Perhaps it speaks to gardeners co-planting pollination-dependent plants with pollinator-attracting plants?

Finally, we found a few instances of plants that are classified as invasive, noxious weeds in the state of Oregon. These include herb Robert (Geranium robertianum) and a cultivar of butterfly bush (Buddleja davidii ‘Ruby Chip’). Note that even though hybrid selections of butterfly bush were previously thought to be sterile, recent work at OSU has shown that this is not the case6.

Next Steps

As we move into Fall and Winter, Taylor and I will continue to work on identifying and classifying garden plants. Taylor has run preliminary analyses on the plant community data, which I hope to share with you on our October 2025 Zoom call. Taylor is also scheduled to present a poster on this work at the 2025 Entomological Society of America meetings in November. Thus, we hope to have all plant identifications vetted by that time, so that we can proceed with more formal analyses.

References

1Loram et al. (2008). Urban domestic gardens (XII): the richness and composition of the flora in five UK cities. Journal of Vegetation Science, 19(3), 321-330.

2Avolio et al.. (2018). Biodiverse cities: the nursery industry, homeowners, and neighborhood differences drive urban tree composition. Ecological Monographs, 88(2), 259-276.

3Cubino, et al. (2020). Linking yard plant diversity to homeowners’ landscaping priorities across the US. Landscape and Urban Planning, 196, 103730.

4Avolio, M., Blanchette, A., Sonti, N. F., & Locke, D. H. (2020). Time is not money: income is more important than lifestage for explaining patterns of residential yard plant community structure and diversity in Baltimore. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 85.

5Wheeler, M. M., Larson, K. L., Cook, E. M., & Hall, S. J. (2022). Residents manage dynamic plant communities: Change over time in urban vegetation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 944803.

6Still, C., & Contreras, R. (2024). Relative fecundity and ploidy of 34 Buddleja cultivars. Journal of Environmental Horticulture, 42(4), 148-164.

Garden Ecology League Meeting

October 16, 2025, 12:00pm – 1:00pm

Via Zoom

Join Zoom Meeting:

Agenda

Noon Welcome Sherry

12:05 Lab update W/ focus on the pollinator garden study Gail

12:30 Questions & discussions / Interest in research All

12:55 Wrap up Sherry

Mark your calendar for 2026

- March 19, 2026, noon – 1 pm, meeting via Zoom

- October 15, 2026. Noon-1 pm, meeting via Zoom

- TBD – We plan to offer an in-person event during the summer